Relations

Relations are super useful and a basic concept in many areas of mathematics and computer science. We can build this concept basically directly from what we learned from set theory. You already know many examples, like and , and so on. We will also see that functions are simply relations with a special property.

Definition 3.9: A (binary) relation from a set to a set (also called an - relation) is a subset of . If , then is called a relation on .

Oftentimes we will see something like:

Given some relation on that is ..., prove that fulfills ...

Intuition

Don't use intuition to argue or prove something. This is only meant to be to get an idea of a proof, on logic level, or to get an idea of whether some statement is true or false. For example, statements like there is a relation that is ... and .... Additionally, this intuition will probably make it easier to find counterexamples. But still, you have to always argue using definitions and logic.

Graphs

This is not to be confused with Hasse Diagrams for partial order relations

Really, if you think about a relation (i.e. a relation which is defined on one set , which might be generic) and you have some property, think about the directed graph representation of this property - draw it! Oftentimes, this feels like cheating, because some exercises seem trivial when looking at them in graph representation. After learning about graphs in A&D, you might even be tempted to think about what the different graph algorithms and properties mean in the context of relations.

So what is the graph representation?

-

We use nodes to depict elements of the set . Of course, oftentimes is an arbitrary/generic set, we can still draw some dots for the elements of to try to understand the structure of the relation.

-

For each element draw an arrow from node to node . If we again have some generic relation, that satisfies certain properties, try to understand how these properties are represented in your graph. I will elaborate on it in the section on properties. However, it is a good practice to do so.

Example: Consider the set and the relation

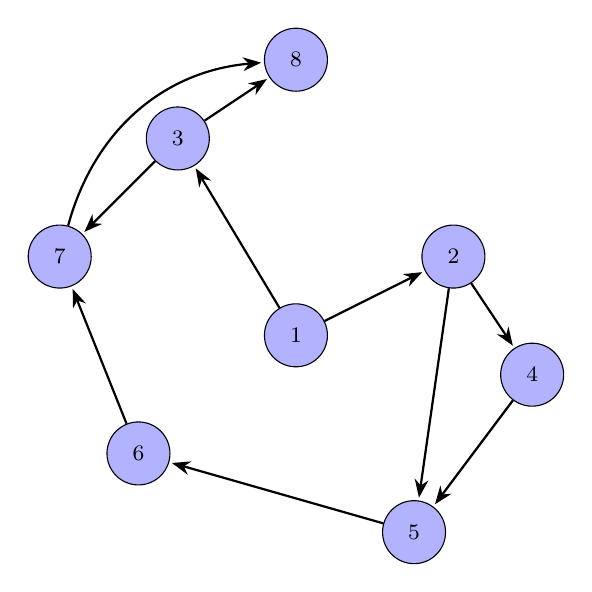

Then we obtain the following graph representation

Simple graph representation - by Tobias Steinbrecher

Matrices

The formalities defined in this section on matrices are not covered in the lecture. However, it might help deepen the understanding of the topic.

For relations on finite sets we can also represent relations as matrices in where and . The matrix representation gives us an additional tool for understanding different properties and operations on relations.

Let and , . We define as follows:

Thus

Example

Let and . Then:

Matrix Operations

In Linear Algebra we have seen component-wise addition on matrices. Here we will define similar component-wise operations (OR) and (AND). Note that these definitions are the same as in LinAlg but since these matrices contain truth values instead of numbers, we define scalar addition as OR and scalar multiplication as AND.

In Algebra (chapter 5) you will see that these operations correspond to addition and multiplication on the field and the matrices are elements of the vector space .

Thus

We define standard matrix multiplication again using OR as addition and AND as scalar multiplication:

Operations on Relations

Proven by intimidation or alternatively by the reader, we can find the following correspondence between operations on relations and operations on matrices:

For a relation on we further find that

The transitive closure of a relation can be determined algorithmically using the following pseudocode. It can be shown that the while loop terminates after at most iterations.

A = zero_matrix(n,n)

B = matrix(\rho)

while A != B:

A = B

B += B.multiply(B)

return ASpecial Relation Matrices

Theory

Properties

Reflexive Relations

A relation is called is called reflexive, if for all :

To prove reflexivity of a relation, we often start with something like:

Let be arbitrary...

Then our goal is to derive that (from some given properties about ).

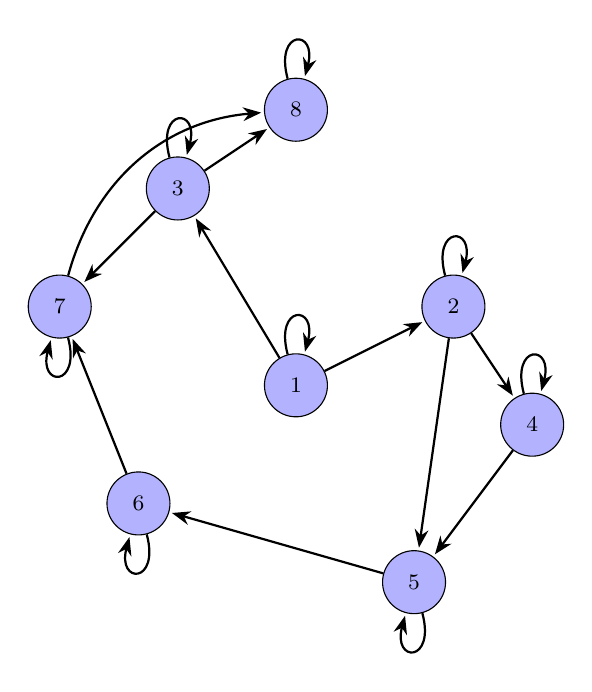

In the graph visualization of a reflexive relation, we must have a self-loop at each node:

Example of a graph of a reflexive relation - by Tobias Steinbrecher

Irreflexive Relations

A relation is called irreflexive if for all :

Symmetric Relation

A relation is called symmetric if for all :

To prove symmetry of a relation, we often start with something like:

Let be arbitrary, such that .

Therefore

In the graph representation, all the edges have to go in both directions:

Example of a graph of a symmetric relation - by Tobias Steinbrecher

Transitive Relations

A relation is called transitive if for all :

To prove transitivity of a relation, we often start with something like:

Let be arbitrary, such that and .

Therefore

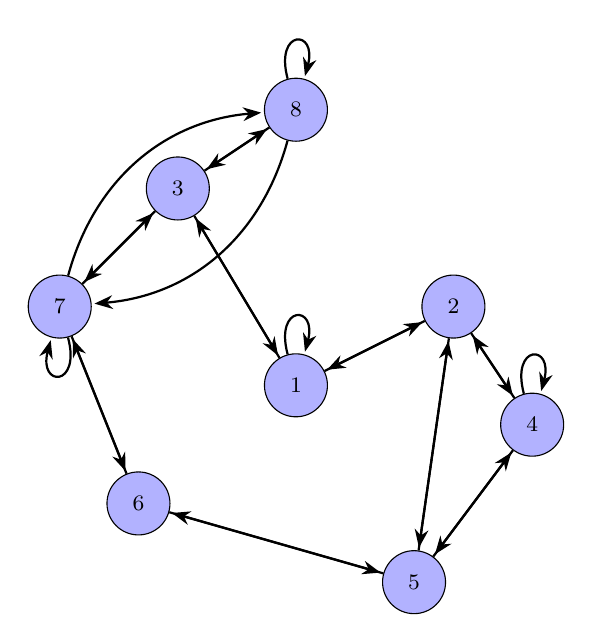

The following graph is an example of a transitive relation

Example of a graph of a transitive relation - by Tobias Steinbrecher

Antisymmetric Relation

A relation is called antisymmetric if for all :

To prove antisymmetry of a relation, we often start with something like:

Let be arbitrary, such that and .

Therefore

In the graph of an antisymmetric relation, it can never be the case that there is an edge from node to and an edge from node to . Otherwise, the two elements corresponding to the nodes would have to be equal, which is a contradiction, as we draw different nodes for different elements.

Equivalence Relations

An equivalence relation needs to satisfy three properties:

An equivalence relation is a relation over a set which satisfies reflexivity, symmetry and transitivity.

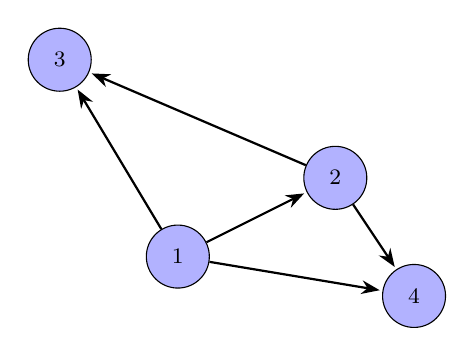

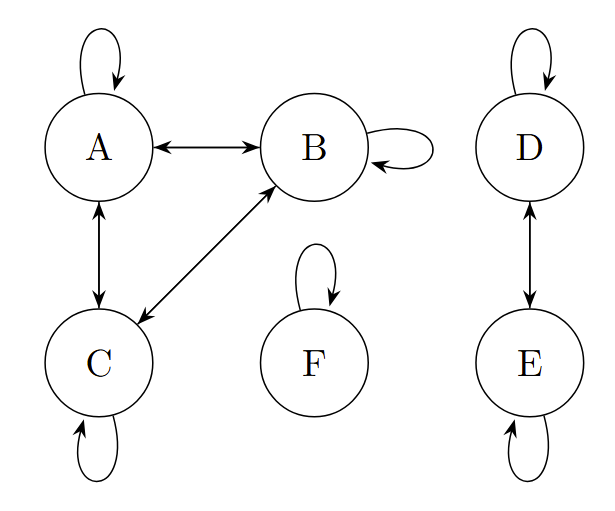

This means to show that a relation is an equivalence relation, we simply need to confirm all of the three properties one by one. To disprove that a relation is an equivalence relation, it is enough to disprove one of the properties (often using a concrete counterexample). The graphs of equivalence relations look like this:

Example of a graph of an equivalence relation

We can see that the graph is divided into connected components. Symmetry and transitivity ensure that an element is either connected to all other elements in a component or none. This motivates the following definition:

Equivalence classes

For a set with an equivalence relation , the equivalence class of a is a set including all elements which are in relation with :

Intuitively, an equivalence relation builds a "complete" connection between the elements in an equivalence class. For example, for the relation in the picture above we would have:

Note that the same equivalence class can have multiple notations. Here .

Equivalence classes of an equivalence relation over form a partition of :

A partition of a set is a set (for some index set ) which satisfies two properties:

- for

The sets in a partition are disjunct while "covering" the entire set . We name the set of all equivalence classes of over the quotient set of by and write . Since is a partition of , this means that every element of is contained in exactly one equivalence class.

Partial Order Relations

Hasse Diagrams

Special Elements in Posets

Lattices

Exercises

Verifying Properties

Commutativity of MatricesDifficulty: 2/5Relevance: 🎓🎓Source: Tobias Steinbrecher

Let be the set of all matrices over the reals. Define a relation on by

Prove or disprove the following properties:

- is reflexive

- is symmetric

- is transitive

Less ThanDifficulty: 4/5Relevance: 🎓🎓🎓🎓Source: Yannick Funke and Philipp Barski

For any poset we can define a relation on such that

Prove that is irreflexive, antisymmetric, and transitive.

Ad-hoc

Collatz ConjectureSource: Max Obreiter

The Collatz Conjecture (opens in a new tab) states that for any positive integer , the following sequence will eventually reach 1:

Give a formula in predicate logic that is true iff the Collatz Conjecture is true. (Note that predicates are not allowed to be recursive.) The universe should be .

Equivalence Relations

Intersection of equivalence relationsSource: Lemma 3.10

Let and be equivalence relations on a set . Prove that is also an equivalence relation on .

Equivalence Relation on Vector SpacesDifficulty: 3/5Relevance: 🎓Source: Tobias Steinbrecher

Let be a real vector space, and define a relation on as follows: For , we say if and only if , where is a subspace of . Prove that this relation is an equivalence relation.

Lattices

Missing joinDifficulty: 4/5Relevance: 🎓🎓🎓Source: Max Obreiter/GCA Ex. 10.21

Let be a finite poset with the greatest element . Show that if every pair of elements has a meet, then is a lattice, i.e. every pair of elements has a join.

Source: HS24 Geometry: Combinatorics and Algorithms, Chapter 10 Exercise 10.21 (opens in a new tab)

Combinatorics

Once upon a time, in the mystical land of Lernphase, there came a fateful day when I innocently decided to tackle some "quick exercises" on relations. Easy, right? I'd seen problems like, "How many reflexive relations are there on a set of elements?" before. Armed with some intuition from graph theory and a sprinkle of combinatorics, I managed to crack it. "Not bad," I thought. "This was actually a fun exercise!" (Feel free to try it below.)

But then I started wondering... What if they ask about symmetric relations? What about transitive ones? What if they combine different properties? Damn! And what about partial order relations or equivalence? That's when things started to spiral. In the spirit of thoroughness, I began constructing this giant table, trying to work out every possible combination myself. I figured I could add the formulas to my cheat sheet later. Little did I know what I was getting into.

I really should have read the Wikipedia article beforehand—because when I got to transitive relations, I was stuck for hours. There was no simple solution in sight. At some point, I thought, "Surely, they won't ask this on the exam.". But something wouldn't let me quit. So, I first shifted to counting partial order relations, thinking they might be easier since they have more structure. Still, I couldn't let go of the problem.

In a last-ditch effort, I started writing brute-force programs to count relations and derived some recurrences that seemed to work. Of course, verifying this recurrence and brute-forcing larger sets wasn't feasible because there were just too many possibilities.

I won't tell you how it ended. You'll have to figure that out yourself! But you'll definitely learn a lot about combinatorics and graphs in the process.

Check out the problems below. The first few are good practice, but if you're feeling adventurous, try the hard ones! Otherwise, skimming the Wikipedia (opens in a new tab) article first might save you some headaches.

Number of relationsSource: Max Obreiter

How many relations are there from a finite set to a finite set ?

Number of reflexive relationsSource: Tobias Steinbrecher

How many reflexive relations are there on a set of elements?

Number of symmetric relations

How many symmetric relations are there on a set of elements?

Number of Irreflexive Relations

How many irreflexive relations are there on a set of elements?

Number of antisymmetric relations

How many anti-symmetric relations are there on a set of elements?

Number of Reflexive and Symmetric Relations

How many relations are both reflexive and symmetric on a set of elements?

Number of Equivalence RelationsDifficulty: 5/5Relevance: 🪩Source: Tobias Steinbrecher

How many equivalence relations are there on a set of elements?

Number of transitive relationsDifficulty: 🐉Relevance: 🪩

How many transitive relations are there on a set of elements?

References

To delve deeper into this topic the Wikipedia Article (opens in a new tab) is actually quite interesting and not bloated with stuff that involves higher-level mathematics.