under construction

Group Theory

Group theory is a fascinating area of mathematics. It reveals deep connections between seemingly unrelated fields, from cryptography to quantum mechanics. The concept of a "group" provides a unifying framework to study symmetry and structure.

The most central definition is the definition of a group:

Definition 5.7: A group is an algebra , where:

- Associativity: For all , .

- Identity Element: There exists an such that for all , .

- Inverse Element: For each , there exists such that .

Note that we assume that , thus we have closure.

Note that these axioms are not minimal.

Theory & Intuition

Direct Product of Groups

Definition 5.9: The direct product of groups is the algebra:

where the operation is defined component-wise:

Lemma 5.4: is a group, where the neutral element and the inversion operation are defined component-wise in the respective groups.

Why are these product groups interesting? Well, as we will see in the following subsection, the notion of an isomorphism provides a way to sort of say two groups have the same structure. In that sense, being able to find an equivalent form written as a direct product of smaller groups, can be very helpful.

Homomorphisms & Isomorphisms

Definition 5.10: For two groups and , a function is called a group homomorphism if, for all :

If is a bijection from to , then it is called an isomorphism, and we say that and are isomorphic and write .

What does this actually mean? It sort of means, that it does not matter if we apply the map first and compute the group operation (in ) and then look at the result in or if we compute the product (in ) and the apply the homomorphism and look at the output in . Both ways yield the same result if the equation above holds. So one could intuitively say the role of an element when computing the group operation with some other element in , is preserved through the mapping . While this observation and description is very imprecise, the following section should make the intuition behind this kind of preservation clear. The little property from above actually lets us derive more nice properties of . Namely:

Lemma 5.5: A group homomorphism from to satisfies:

- ,

- for all .

Intuition about Homomorphisms

Why does a homomorphism map the neutral element in to the neutral element in ? Well, this is exactly what we would expect intuitively. The neutral element in a group is like "doing nothing" to an element - it's the identity operation. If we apply after has acted on , it should produce the same result as letting map first and then applying .

But here's something interesting: does every homomorphism have to be injective? No! For instance, consider an extreme case where the entire group maps to just the neutral element . This mapping satisfies the homomorphism property because applying the neutral element under any group operation still respects the structure.

A nice way to think of this is like projecting a 3D object onto a flat surface: the object's details might be lost, but the structure of relationships between points can still hold.

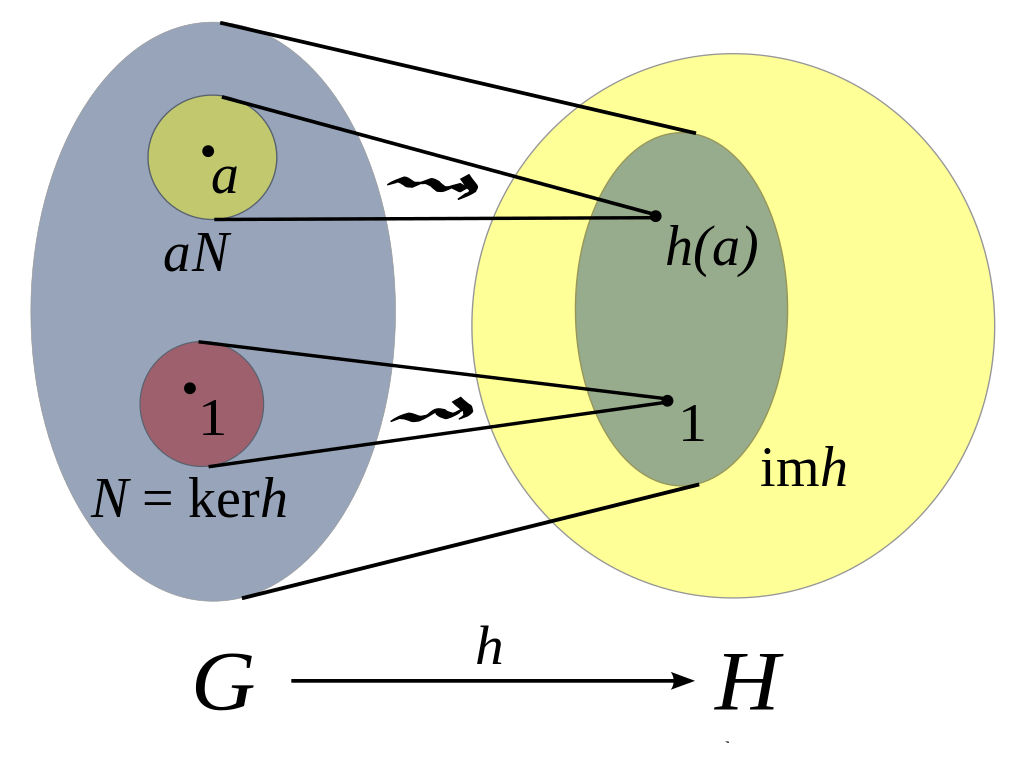

To gain intuition about homomorphisms, I think the following image is incredibly helpful:

Von Cronholm144 - Eigenes Werk, CC BY-SA 3.0, Link

So what's going on in this picture? First of all we have to clarify some naming and notation:

- is a homomorphism in this picture

- is the so-called kernel of the map . This is simply the set of all elements which map to the neutral element. You might have heard of the concept of kernel or null-space in linear algebra. The concept is related - for every linear map (or more concretely matrix), there is some set of elements in the domain, which maps to in the codomain. So in our case it is simply consider the following set:

So as you can see in the picture and as pointed out before, there can be more than one element in the kernel. We could actually have the case that .

- is the so-called image of the map . Again you might have heard about a concept like this in linear algebra. It is simply the set of all elements we can possibly get as an output:

- The set is a so-called coset. This concept is not explicitly stated in this course, but super useful when you explore more properties. You will find more about it in the Cosets section. We defined (i.e. all elements in which map to ). Now for an arbitrary element , we can define:

So what we are doing here is simply taking an element and multiplying it (in the sense of the group operation in ) to all elements which are in and making a set of all the outputs. We can do this in arbitrary , however in this case we choose .

What is interesting about this picture?

-

The kernel forms the foundation of symmetry in - all elements in the kernel behave indistinguishably under .

-

We can sort of see at least in the picture (there is no reason why we should expect/believe this intuitively in the first place!) that there are some sort of classes of elements (e.g. ) which map all to the same value . These can be built from these ominous constructions we call cosets. There is no reason to believe that this is actually true... well there is - after we proved interesting properties which are more investigated below - also take a look at the exercises.

- Think about what would happen in the picture above if was injective!

There are so many more connections here which Let's try to look at a specific example to get a better grasp of what we have done until now.

With this deeper understanding, try exploring homomorphisms in different contexts - like how polynomials, matrices, or symmetry groups map to each other. It's all connected!

Intuition of Isomorphisms

A group isomorphism is a special type of group homomorphism that provides a perfect "translation" between two groups. If two groups are isomorphic, they have the same structure, just represented differently. Every operation in one group corresponds exactly to an operation in the other group under the isomorphism. Importantly, the correspondence is bijective, meaning it pairs every element of one group with a unique element of the other group and vice versa.

An isomorphism between two groups and is a bijective map such that:

- for all (preserves the group operation).

- is a one-to-one and onto mapping (bijective).

If such a map exists, and are said to be isomorphic, denoted .

Analogy: Think of two jigsaw puzzles that look completely different on the surface but are constructed from pieces with identical shapes. You can perfectly match every piece in one puzzle with a piece in the other puzzle, and the way the pieces fit together is preserved. The isomorphism is the "perfect match" function that pairs each piece in one puzzle with the corresponding piece in the other.

In the same way, group isomorphisms preserve the "shape" of the group's structure, ensuring every element and operation in one group corresponds to those in another.

When thinking about a set of all possible groups. It is the case that the relation is an equivalence relation. Now it really gets interesting. We could now ask questions like how many different groups (in the sense of equivalence classes) are there that have elements? There are super interesting results about this question. For example that if is prime, there is only one group, i.e. all groups of order are isomorphic.

Steps to Prove an Isomorphism

To rigorously prove that two groups and are isomorphic, follow these steps:

-

Define a Candidate Map: Identify a function that you suspect to be an isomorphism.

-

Verify the Map is Well-Defined: Ensure that the proposed map is unambiguous and consistent. That is, for any , is uniquely determined.

-

Verify the Map is Totally Defined: Confirm that the map is defined for all elements of (i.e., applies to every element of ).

-

Verify the Map Maps to the Codomain: Ensure that for all , so that the image of lies entirely within .

-

Check the Homomorphism Property: Verify that for all . This ensures the map preserves the group operation.

-

Check Injectivity: Prove that is one-to-one by showing that if , then .

-

Check Surjectivity: Prove that is onto by demonstrating that for every , there exists such that .

-

Conclude Isomorphism: If the map satisfies the homomorphism property, is well-defined, maps to the codomain, and is bijective, then is an isomorphism, and .

Example

Prove that .

Step 1: Define a Candidate Map

Define by:

where denotes the remainder when is divided by (i.e., ).

Step 2: Verify the Map is Well-Defined

The group consists of integers modulo 6. For any , and are uniquely determined remainders modulo 2 and 3, respectively. Since remainders are unique, produces unique and consistent pairs . Thus, is well-defined.

Step 3: Verify the Map is Totally Defined

The map is defined for all . Since and exist for any integer , is totally defined.

Step 4: Verify the Map Maps to the Codomain

The codomain is , where and . For any , and , so . Thus, maps into the codomain.

Step 5: Check the Homomorphism Property

Let . We can compute

(where means addition modulo , i.e. we take remainder modulo after doing addition).

Using the modular arithmetic property , we have:

On the other hand:

Therefore

Thus, preserves the group operation.

Step 6: Check Injectivity

Assume . Then:

This implies:

Hence, and . By the Chinese Remainder Theorem (as ), . Thus, in , and is injective.

Step 7: Check Surjectivity

For any , where and , the Chinese Remainder Theorem () guarantees the existence of an integer such that:

By construction, , and . Thus, is surjective.

Step 8: Conclude Isomorphism

Since is well-defined, totally defined, maps to the codomain, preserves the group operation, and is bijective, is an isomorphism. Therefore, .

Subgroups

Order

Cyclic Groups

Lagrange Theorem

Lagrange's Theorem states:

If is a finite group and is a subgroup of , then the order (number of elements) of divides the order of .

We want to prove this theorem here! Because it illustrates interesting concepts and provides deep insights into the structure of groups

Useful Definitions

Definition (Left Coset): Let be a subgroup of , and let . The left coset of with respect to is the set:

Key Properties of Cosets

Lemma (Equal Size of Cosets): Every left coset has the same number of elements as the subgroup . Specifically, .

Proof: Define a map by . We show that is a bijection:

-

Injectivity: Assume . Then:

Multiplying on the left by , we get . Thus, is injective.

-

Surjectivity: Let . By definition of , for some . Thus, there exists such that . Hence, is surjective.

Since is both injective and surjective, it is a bijection, and .

Lemma (Disjoint or Equal Cosets): If , then .

Proof: Assume . Then there exists , so and . Thus:

for some . Rearranging, we get:

Since (because is a subgroup), . Let , so:

Now consider any element . By definition, for some . Substituting , we get:

Thus, . By symmetry, . Hence, .

Lemma (Cosets Partition ): The cosets form a partition of , meaning:

- Every element of is in some coset .

- Two cosets and are either disjoint or identical.

Proof:

- By definition of a coset, for any , . Thus, every element of is in at least one coset.

- By the previous lemma, if , then . Otherwise, . Hence, the cosets are either disjoint or identical.

Proof of Lagrange's Theorem

Let be a finite group and a subgroup of . By the lemmas above, the cosets partition . Let be the number of distinct cosets. Since each coset has size and the cosets are disjoint, the total number of elements in is:

where is the number of cosets (the index of in ). Thus, divides .

Euler's Totient Function and multiplicative groups

RSA

Digressions

Cosets

Finite Abelian Groups

A fundamental result for finite abelian groups is the Fundamental Theorem of Finite Abelian Groups, which states that every finite abelian group is isomorphic to a direct product of cyclic groups of prime power order.

Representation Theory

Representation theory studies groups by representing their elements as matrices or linear transformations. This approach is widely used in quantum mechanics, crystallography, and other fields.

Exercises

Finite group of even orderDifficulty: 2/5Relevance: 🎓🎓🎓Source: Abstract Algebra: Theory and Applications

Show that if is a finite group of even order, then there is an such that is not the identity and

Subgroups of a Cyclic GroupDifficulty: 3/5Relevance: 🎓🎓🎓🎓Source: Tobias Steinbrecher

Let be a cyclic group. Prove that every subgroup of is cyclic.

The Square RootDifficulty: 2/5Relevance: 🎓🎓🎓🎓Source: Yannick Funke

Let be a (finite) group of odd order. Define the operation such that

Show that is a bijective, well- and totally defined function.